Joe Scutellaro had nine cents to his name when he entered the poormaster’s office on February 25, 1938. His family’s last grocery order had been five weeks before. The amount had been so paltry, the Scutellaros had mostly subsisted on stale rolls and borrowed coffee.

Always a small man, Joe had lost so much weight his worn green suit hung off his bony frame.

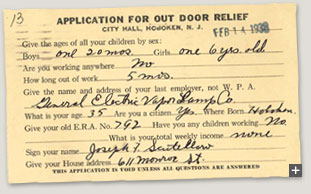

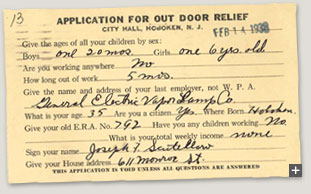

One of many applications Joe Scutellaro

One of many applications Joe Scutellaro

submitted to the poormaster.

He had tried repeatedly to get assistance. During his last visit to the poormaster’s office, Harry Barck had handed him a stack of aid applications, implying that sending just one would not be enough. Scutellaro had sent in an application every other day, for ten days, with no response. Finally he went to City Hall, and after waiting a while, was called into the poormaster’s inner office.

Within a half-hour, Poormaster Harry Barck would be pronounced dead.

Scutellaro would later say that the Hoboken poormaster had denied him another relief check and suggested his wife work as a prostitute instead. A scuffle ensued. When Harry Barck fell across his desk, Scutellaro said, he landed on top of a desk spindle, a sharp metal spike he used to stack rejected applications.

Hoboken’s poor—mostly residents of the city’s downtown “Italian colony”—responded with disbelief, then giddy satisfaction, that they were rid of the old tyrant who had made them beg for a few pieces of coal or a nickel’s worth of day-old bread. When Joe Scutellaro was lead out of City Hall in handcuffs, a waiting crowd cheered him.

Always a small man, Joe had lost so much weight his worn green suit hung off his bony frame.

One of many applications Joe Scutellaro

One of many applications Joe Scutellarosubmitted to the poormaster.

Within a half-hour, Poormaster Harry Barck would be pronounced dead.

Scutellaro would later say that the Hoboken poormaster had denied him another relief check and suggested his wife work as a prostitute instead. A scuffle ensued. When Harry Barck fell across his desk, Scutellaro said, he landed on top of a desk spindle, a sharp metal spike he used to stack rejected applications.

Hoboken’s poor—mostly residents of the city’s downtown “Italian colony”—responded with disbelief, then giddy satisfaction, that they were rid of the old tyrant who had made them beg for a few pieces of coal or a nickel’s worth of day-old bread. When Joe Scutellaro was lead out of City Hall in handcuffs, a waiting crowd cheered him.

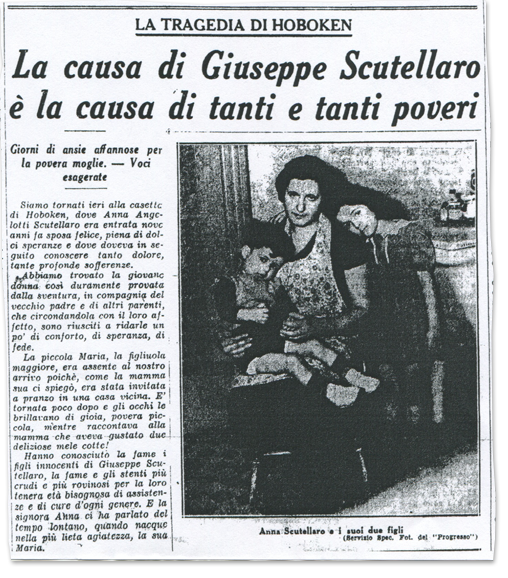

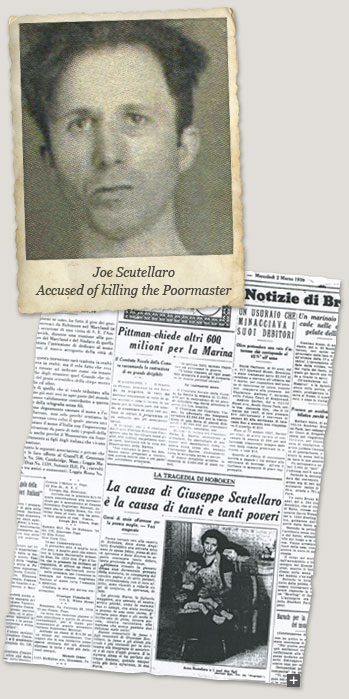

In addition to nationwide coverage in English-language newspapers, the Scutellaro case was closely followed in Il Progresso Italo-Americano, the most popular Italian-language daily in the United States. This March 2, 1938 article is entitled “Guiseppe Scutellaro’s Cause is Shared by Many, Especially the Poverty Stricken: The Tragedy in Hoboken.”