Harry L. Barck

Harry L. BarckHoboken poormaster

Nevertheless, Harry Barck had been crueler and more tightfisted than most: he was said to have incensed the man accused of his murder—an unemployed mason named Joseph Scutellaro—by recommending that the applicant’s wife work as a prostitute rather than seek public aid.

The killing electrified the city. Uptown power brokers declared Barck “a martyr to civic duty,” while the poor grimly hoped his death would force a change in the way relief was handled in Hoboken.

Within hours wire services broadcast the news nationwide. The Scutellaro case leapt into the headlines. Some editorials questioned: Is this what the country had come to? Men so desperate and humiliated, so lacking in opportunity, they might grow violent? In 1938, millions of Americans were jobless. Private charities had been overwhelmed years before, and federal work projects, when they finally came, were limited. The only recourse for many destitute men and women had been to beg local poormasters for scraps. How long could they go on this way? Some predicted the poor would rise up. Four years before the killing of the Hoboken poormaster, a writer had watched hundreds of half-starved men wait for hours to apply for aid. Most left empty-handed. Lacking political organization, she noted, each man suffered individually. “But I wonder if some day, crazed and despairing, they won’t revolt without organization,” she wrote an administrator of federal aid. “It seems incredible that they should go on like this, patiently waiting for nothing.”

Judge Charles DeFazio worked in the city’s law department in the 1930s. Listen to his recollections of the poormaster and the jobless poor. LISTEN

Judge Charles DeFazio worked in the city’s law department in the 1930s. Listen to his recollections of the poormaster and the jobless poor. LISTEN

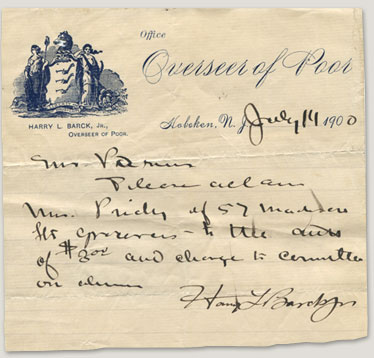

The poormaster’s letter to a grocer, allowing a

The poormaster’s letter to a grocer, allowing aclient to receive three dollars worth of groceries.

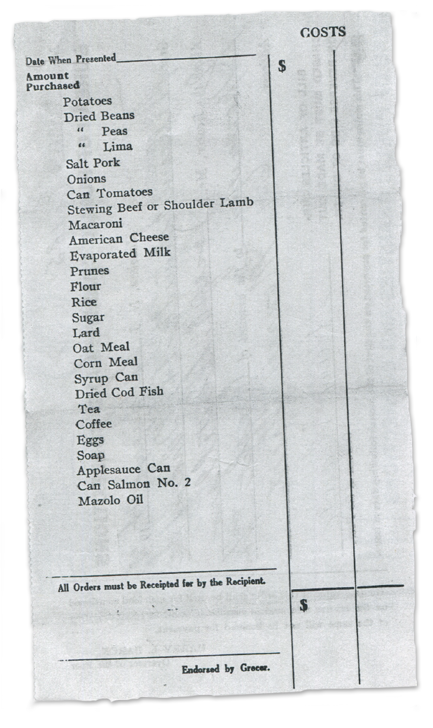

Poormaster’s grocery form. Poormasters determined whether applicants received food or clothing or medicine or coal—and precisely how much.

The poormaster’s bread tickets, to be exchanged for day-old bread.